Me: “Okay, coffee’s ready. Can I keep you a bit longer—just a bit?”

Dad: “If coffee is involved, yes. A warm cup is perfect now that the air’s turning autumn-like.”

Me: “You said something earlier that stuck with me: the R function we use depends on the outcome. I didn’t really get that part. In my head, data are just…numbers? What’s there to distinguish?”

Dad: “They’re all numbers, yes. But for statistics, the type of data matters more than people expect.”

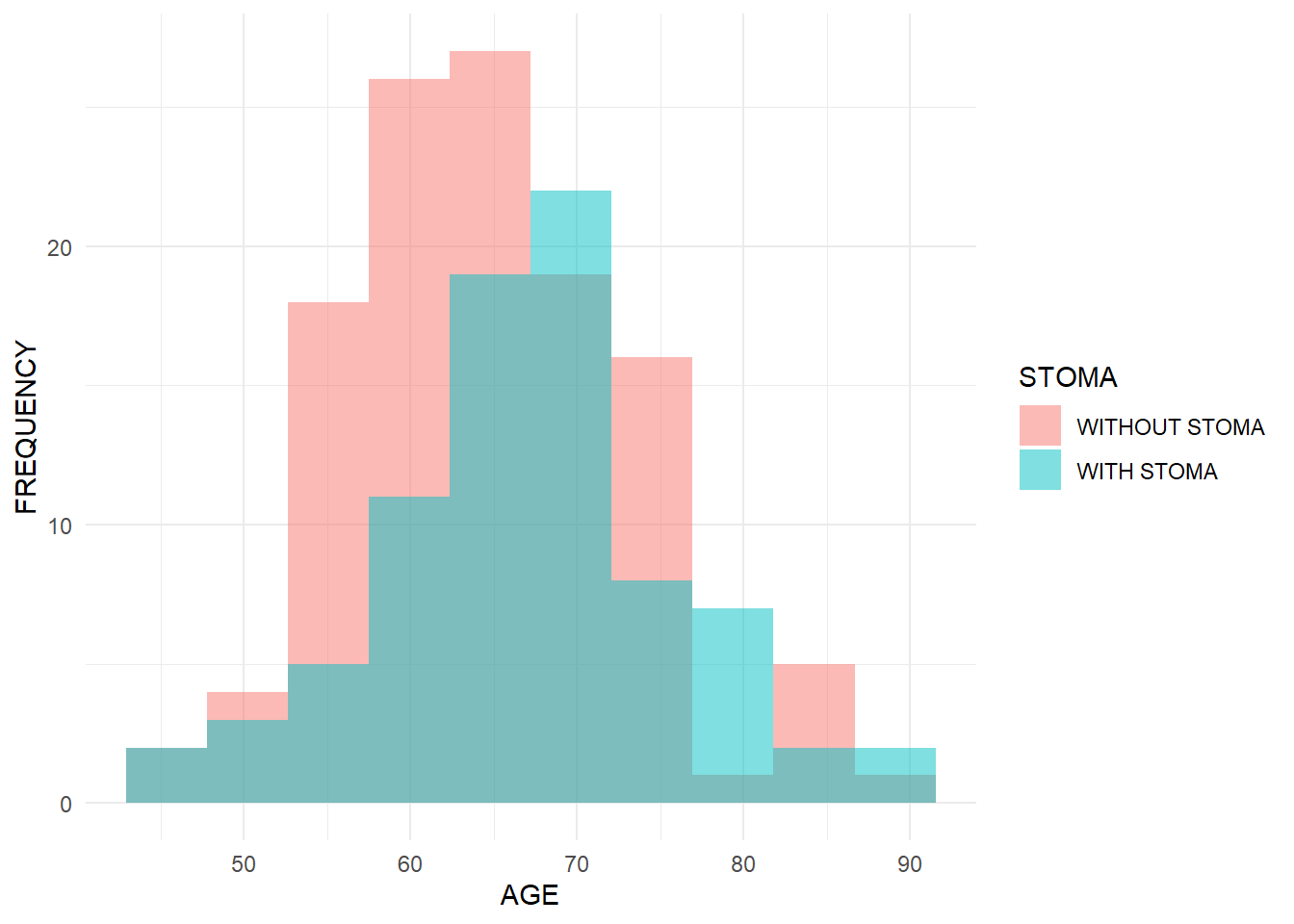

Me: “Continuous data are things we measure, right? Like age or blood pressure. Binary data I get — like ‘with stoma’ vs ‘without stoma’ in my survey.”

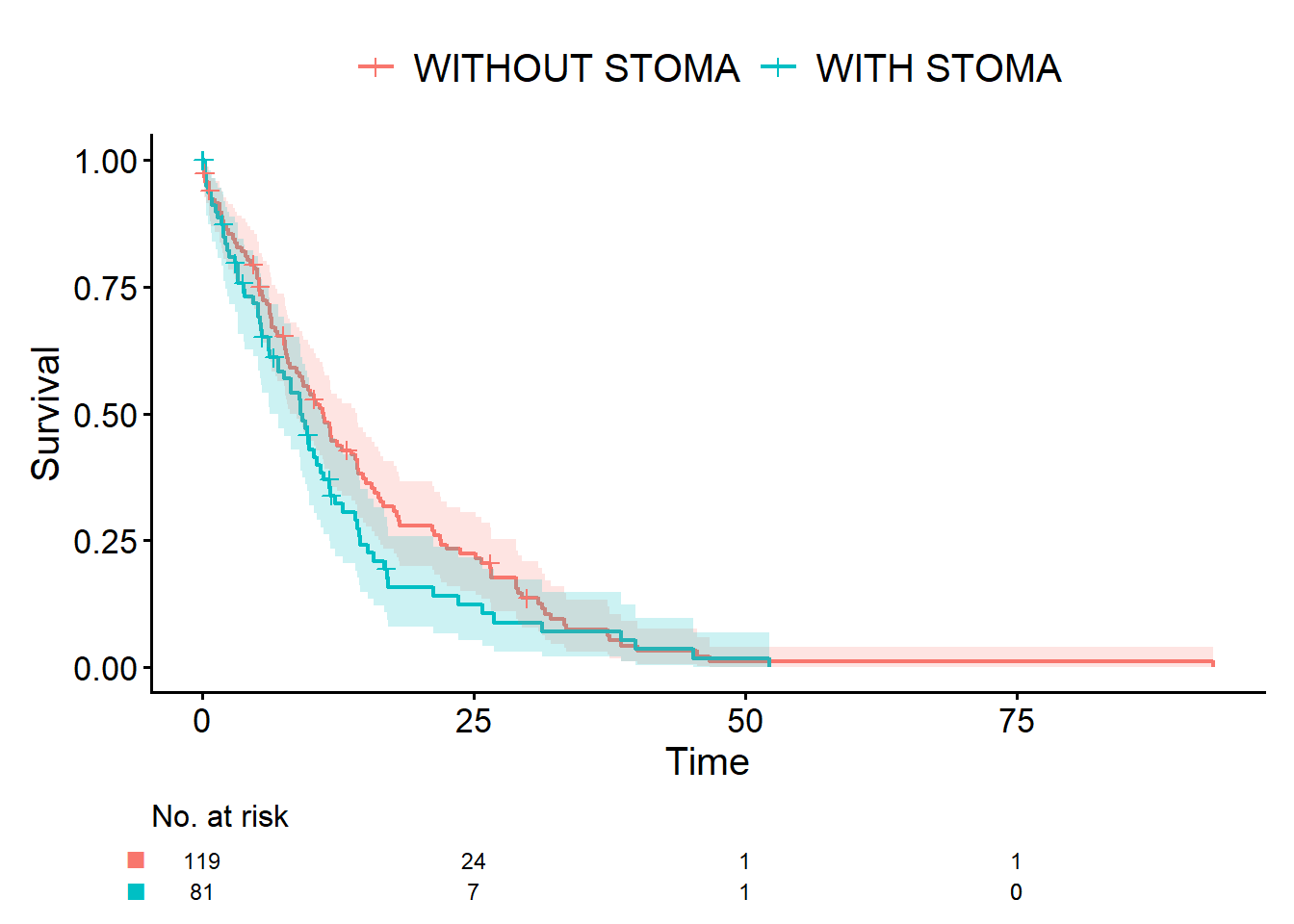

Dad: “Perfect. Count data is when you literally count events, like the number of traffic accidents. Survival data is things like lifespan — time from some starting point until an event, such as death. In your case, that could be time from surgery to returning to work, or time to relapse.”

Me: “When you say it like that, they definitely feel like different beasts. But in the R course I took, we just typed whatever they put on the slides — t.test(), glm(), survfit(), all those things felt like magic spells.”

Dad: “That’s a common side effect of R lectures. Do you have your laptop?”

Dad: “Your laptop. You brought it, didn’t you? Let’s install RStudio.”

Me: “…Well, I did ask for help, so fine.”

Dad: “In R, for continuous data you often use functions like mean() or t.test().”

Dad: “To summarize binary data you can use table(). For p-values, fisher.test(). For more complex analyses, regression models like glm(family = binomial). For survival data, you’ll see functions like survfit(), coxph(), and cifplot().”

Me: “There is no way I can memorize all that. In class I just typed whatever they put on the slides. Those functions are basically incantations to me.”

Dad: “You don’t need to memorize them—not all at once, at least.”

Dad: “What matters is being able to picture which functions belong to which type of data. Or even better, imagining which probability distribution is being assumed.”

Me: “Probability distribution?”

Dad: “You learned this as an undergrad, didn’t you? You’ve heard of the normal distribution — and binomial distribution?”

Me: “At least that one, yes.”

Dad: “Almost any statistical method beyond simple description rests on some kind of probability model. Normal distributions for continuous data, binomial distributions for binary data, Poisson distributions for count data. For survival data, there isn’t a single standard model, but the simplest is the exponential distribution. You don’t have to remember the formulas, just the general matching.”

Me: “So it’s more about rough matching than exact formulas.”

Me: “I don’t know Poisson and exponential. Aren’t those basically curse words?”

Dad: “Yeah, I agree it doesn’t sound like something humans would use. Statistical terms are often the hardest part. If a word ever feels unclear, feel free to come back to it anytime. Anyway, the key is to learn the patterns—which probability model to use for which data type.”

Me: “Uh-huh. And what does that have to do with R?”

Dad: “Quite a lot. I really want you to remember this, there are two common measures: proportions and rates. We use them all the time, like ‘traffic accident rates’. But in everyday language we don’t distinguish them clearly. In statistics, though, a proportion is the parameter of a binomial distribution, and a rate is the parameter of a Poisson distribution.”

Me: “Proportions and rates… aren’t they basically the same thing? I’ve never really distinguished them.”

Dad: “No, they’re not. A proportion is usually a percentage, say, ‘60% of patients are women’. But consider ‘the annual traffic accident rate in Tokyo’. You wouldn’t naturally express that as a percentage. You’re counting events and dividing by person-time or by years.”

Me: “Hmm…go on, professor.”

Dad: “You don’t need rigid textbook definitions. It’s enough if your brain can think: ‘This looks like continuous data, probably close to a normal distribution, then you’ll use functions in this area,’ or ‘This is 0/1 data, so you’ll look for binomial-type functions.’ If you can connect data types and distributions, R functions become much easier to recall.”

Me: “I see. So if I imagine the data type and its distribution, I don’t have to memorize R functions by brute force. That does sound efficient.”

Dad: “Exactly. Once you have that mental image, when you later read manuals or books, you’ll think, ‘Oh, this is that thing I was imagining,’ and everything clicks together. Okay, let me show you a quick demo in R. We’ll simulate age (continuous), sex and stoma status (binary), and survival time, and run simple analyses. We will use the normal distribution, binomial distribution, and exponential distribution.”

Me: “There it is again, the spell-casting.”

Dad: “Pretty much. For now, type library(ggplot2) and library(cifmodeling). I’ll show you a histogram and Kaplan-Meier curves.”

Me: “Fine. I’ll type them with my brain temporarily switched off. That’s how I survived my R class anyway.”

Dad: “Try not to turn your brain off while I’m teaching you. When you add features to R, you use install.packages() and library(). install.packages() installs a package onto your computer, and library() loads that installed package so you can use it.”

Me: “Got it. That actually clears things up a lot. I really did think I had to install it every single time.”

Dad: “Installing every time is like buying coffee beans every time you brew coffee. No one does that. You buy the beans once and just grind when you drink.”