Outcomes: The Bridge from Data Collection to Analysis

Study Design III − Outcomes: The Bridge from Data Collection to Analysis

Keywords: clinical trial, language & writing, research hypothesis, survival & competing risks

What do we mean by “outcome”?

Me: “About that outcome thing we talked about earlier. In our department we read clinical trial papers, and they’re full of abbreviations like DFS and RFS. Those are outcomes too, right? To be honest I don’t really understand them, but everyone uses them as if they were obvious, so it’s hard to ask now. DFS and RFS both seem to be about cancer recurrence. Do you know the difference?”

Dad: “Of course. We often deal with DFS in statistical analyses. The one you probably see most is overall survival (OS). DFS stands for disease-free survival, and RFS stands for relapse-free survival.”

Me: “So relapse-free survival is just the number of days until recurrence?”

Dad: “If we were literally measuring ‘time to recurrence’, I’d probably call that relapse-free time. When we focus on recurrence, we often talk about the cumulative incidence of relapse, or CIR for short.”

Me: “That just made it worse. Aren’t all of these basically the same?”

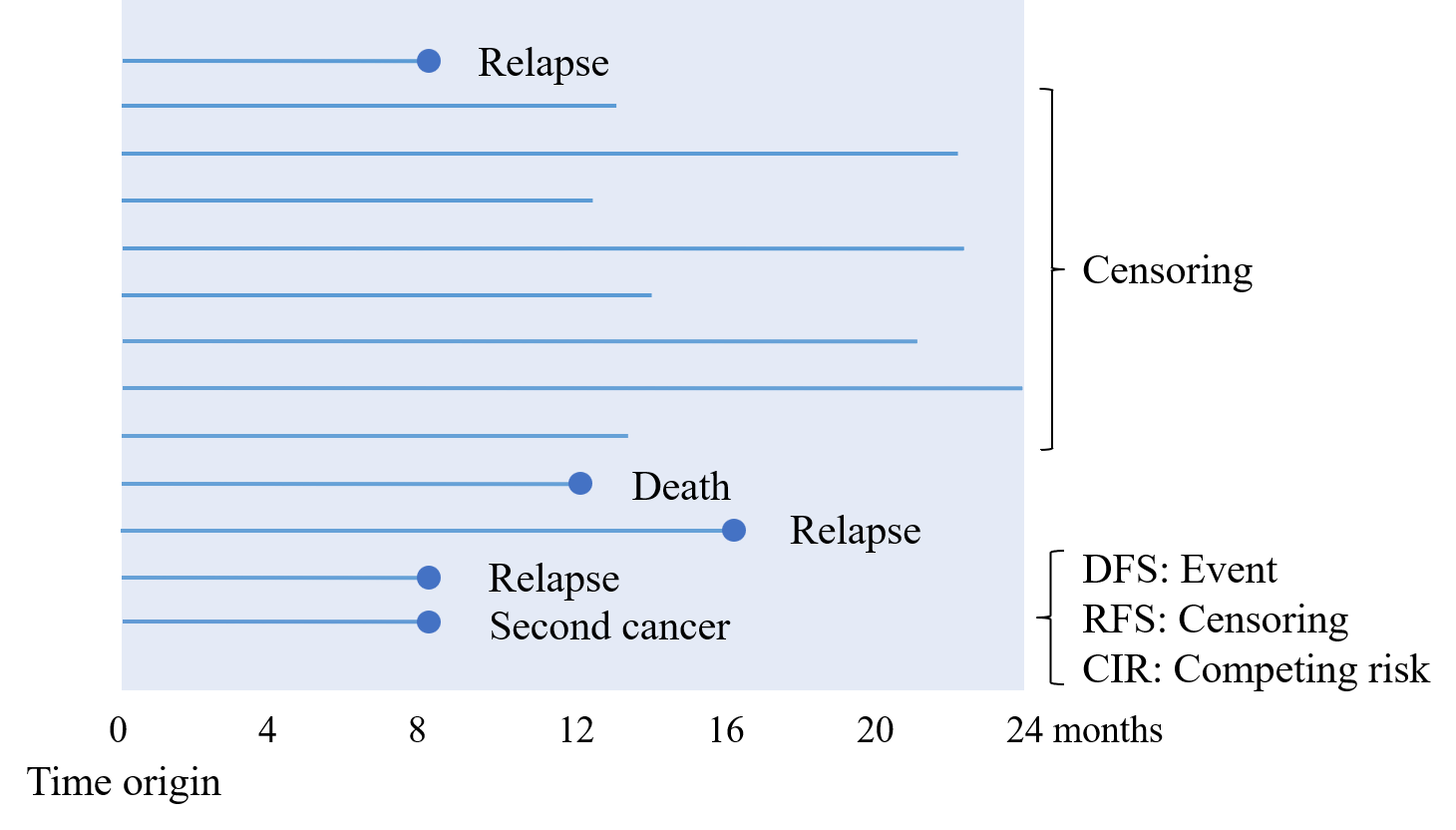

Dad: “In survival analysis, the differences are subtle but important. Think about this: a patient can die without ever having a recurrence. For DFS, the key idea is that we measure the time from the time origin to the first of three events: recurrence, second primary cancer, or death. So not only recurrence, but also death and second cancers are treated as events.”

Me: “What exactly do you mean by ‘treated as events’?”

Dad: “In general, survival time data represent the time until a specified event. To put it simply: suppose you compute the ‘3-year DFS probability’ from DFS data. That corresponds to the probability that no event has occurred by 3 years. In other words, the probability that at 3 years the patient is alive, with no recurrence and no second cancer.”

Me: “Okay, that I can follow.”

Dad: “For RFS, the event is usually defined as recurrence or death. Second cancers are not included. If we were being strict about relapse-free time, then recurrence alone would be the event. Seeing it as a figure would probably make the picture clearer.”

Me: “Mm-hmm. Personally, I feel like DFS is the most important. You’d like to avoid both recurrence and second cancers. Relapse-free time doesn’t feel that meaningful to analyze. And death is the most important event, isn’t it? Why would you leave it out?”

Dad: “You’re right that death is critical. But remember, once a patient has a recurrence and then dies afterwards, they’re already counted as an event for relapse-free survival, even if the death is recorded later.”

Me: “That’s true. If I think about it, deaths that occur before recurrence are often due to things like infections or traffic accidents. Such causes may not be clearly related to the cancer treatment or the cancer itself.”

Dad: “Exactly. In clinical trials, outcomes are often called endpoints. Different trials have different research hypotheses, and endpoints are chosen accordingly. For advanced cancer, we might focus on tumor progression and use progression-free survival. For post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy after curative surgery, we might use relapse-free survival. Let me show you a table summarizing the main survival endpoints in oncology trials (Japan Clinical Oncology Group, 2021).”

| Endpoint | What counts as an event? | censoring date |

|---|---|---|

| Overall survival (OS) | Death from any cause | Last survival confirmation date |

| Progression-free survival (PFS) | Progression or death | Last progression-free confirmation date |

| Relapse-free survival (RFS) | Relapse or death | Last survival confirmation date |

| Relapse-free time | Relapse | Last survival confirmation date |

| Cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) | Relapse only, with death as a competing risk | Last survival confirmation date |

| Disease-free survival (DFS) | Relapse, second cancer, or death | Last survival confirmation date |

| Event-free survival (EFS) | Death, induction failure, relapse, second cancer (depends on trial) | Last survival confirmation date |

| Treatment success time | Death, treatment failure, progression/relapse (depends on trial) | Last treatment-continuation/progression-free confirmation date |

Me: “Nice. This is really helpful.”

Dad: “This table is used when clinical trial groups write their protocols. Protocols are written by a team of clinicians and statisticians. If they don’t define things clearly in advance, everything gets confusing later on. Their motto is ‘one word, one meaning’.”

Me: “Yeah, I can relate. I’m already halfway tangled up.”

Dad: “For OS, the outcome is the time from the time origin of the analysis until death. For DFS, it’s the time from the time origin until whichever happens first: recurrence, second primary cancer, or death. As I mentioned, people also say ‘3-year OS’ or ‘3-year DFS’. In that case we’re not talking about a time, but about the probability at 3 years. Because DFS includes recurrence and second cancers in addition to death, the 3-year DFS probability is necessarily smaller than the 3-year OS probability.”

Me: “Time origin… I’ve never heard that expression before. Can you explain that a bit more?”

Dad: “Sure. Let’s go over a few typical ways of choosing the time origin. DFS is usually used to evaluate what happens after curative surgery, right? So the date of surgery is a natural candidate for the time origin. When the starting point of treatment is clear, like the day of surgery, the choice is relatively easy.”

Me: “Yeah, that’s what I see a lot in papers.”

Dad: “Exactly. On the other hand, if you used the date of discharge as the time origin, then deaths occurring shortly after surgery but before discharge would not be included in the evaluation. Depending on the study, that could easily become a point of criticism. Another common choice is the date of trial registration. In randomized controlled trials, treatment is assigned at registration, so it’s natural to use the registration date as the time origin when drawing survival curves.”

Me: “That makes sense. The exact definitions really do differ a bit from study to study. Actually, I’m in the middle of designing a questionnaire right now. When I told people that you’re ‘picky about outcomes’, it turned out everyone around me was paying more attention to these distinctions than I’d expected. I wanted to properly understand DFS and OS. I’m glad I asked ? I’ll come back for more advice.”

OS, DFS, and RFS are outcomes or endpoints that are frequently used when evaluating the effectiveness of post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy. How are these endpoints chosen and used? One guiding principle comes from how regulatory agencies evaluate anticancer drugs. For example, the Japanese guideline on clinical evaluation of anticancer drugs states that, in order for an anticancer drug to be approved, its efficacy must be demonstrated reliably, typically through evidence such as prolongation of survival. In this framework, overall survival (OS) is treated as a clinical endpoint and given particular weight (Biomarkers Definitions Working Group, 2001).

At the same time, in adjuvant chemotherapy trials, endpoints such as DFS are sometimes adopted as surrogate endpoints. A surrogate endpoint is defined as a measure intended to substitute for a clinical endpoint and expected to predict clinical benefit or harm. The main advantage of using surrogate endpoints like DFS is that trials can be completed in a shorter period of time.

However, past regulatory experience has shown that reliance on surrogate endpoints can lead to misleading evaluations of drugs (Fleming and DeMets, 1996). For example, in advanced colorectal cancer, the combination of 5-FU and leucovorin produced promising tumor shrinkage in clinical trials. Yet when the clinical endpoint OS was evaluated, it became clear that the regimen had little or no effect on survival (Fleming and DeMets, 1996).

This quiz focuses on how we define progression and events when using progression-free survival (PFS) as an endpoint in clinical trials. To measure PFS, we need to determine tumor progression based on imaging. Sometimes a central review committee evaluates images to make this more objective. In that case, there may be discrepancies between:

- the progression date according to the central review, and

- the progression date according to the local investigator.

This issue is called a disagreement between central and local assessment. Which of the following is not appropriate as a way to handle this in a clinical trial?

- In the primary analysis, use the results of the central review, which is considered more objective.

- In the primary analysis, define progression as whichever date comes first: central or local.

- Hold a case review meeting and decide how to handle discrepant cases based on medical judgment.

- Perform two analyses: one using central assessment, and one using local assessment.

- The correct answer is 2.

If you define the event as “whichever progression date comes first (central or local)”, you are more likely to shorten PFS artificially, because you systematically choose the earlier of the two dates. That introduces bias.

This doesn’t mean you must always use central review; in some contexts, local assessment may better reflect real clinical decision-making. But “always take the earlier date” is not an appropriate general rule.

Reference

Biomarkers Definitions Working Group. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2001;69(3):89-95

Fleming TR and DeMets DL. Surrogate end points in clinical trials: are we being misled? Ann Intern Med 1996;125(7):605-13

JCOG protocol manual version 3.8 [Internet]. Tokyo: Japan Clinical Oncology Group; 2025

Episodes, glossary, and R-script

- A Story of Coffee Chat and Research Hypothesis

- Data Have Types: A Coffee-Chat Guide to R Functions for Common Outcomes

- Outcomes: The Bridge from Data Collection to Analysis

- A First Step into Survival and Competing Risks Analysis with R

- When Bias Creeps In: Selection, Information, and Confounding in Clinical Surveys

- Statistical Terms in Plain Language

- study-design.R